First Draft #15: a newsletter on public language

The power of video; Sondheim; spies

Video killed the political star

It’s hard to know when a story will cut through, but one ingredient always ups the odds: video. Just ask Allegra Stratton. Or Matt Hancock. In an age where nothing sticks, embarrassing footage still ends careers.

But how potent is video? Is it really endowed with unique powers of persuasion? It is a question MIT academics recently tested on over 7,500 Americans. They showed test subjects versions of 48 political ads. Some saw video, others read a transcript and some received no information at all. The authors then measured the ads’ credibility (whether participants believed the information) and persuasiveness (whether their minds were changed by it).

They found video performed better than text on credibility, but had a “minimal” advantage on persuasiveness. In other words, video makes a message more believable, but only a tiny bit more convincing. The same was true of all groups, regardless of age, political knowledge or partisan affiliation.

The power of video, the authors suggest, is not that it is inherently more persuasive, but that we are more likely to look at it. "People may prefer watching video to reading text," says MIT’s Ben Tappin. "For example, platforms like TikTok are heavily video-based, and the audience is mostly young adults. Among such audiences, a small persuasive advantage of video over text may rapidly scale up because video can reach so many more people."

Public anger is often too diffuse and amorphous to have political consequences. Viral videos up the pressure by channeling discontent toward a fixed point. This has less to do with the innate magic of the moving image, and more to do with the ease with which clips are shared and consumed today. Video may be little more persuasive than text, but it can, in minutes, get a nation talking about the same thing. And that is why it is politically lethal. @AlexDymoke

Farewell the greatest lyricist

Last week Bob Dylan finally became the world’s finest lyricist. The accolade has been a long time in coming and it has only happened now because the holder of the title, Stephen Sondheim, died at the age of 91.

In Finishing The Hat, his brilliant collection of lyrics and observations on song writing, Sondheim explains the difference between a lyric and a poem. A lyric, he says, is best displayed in a musical setting. A poem, by contrast, has an insidious music of its own and is usually diminished when set to music. Vaughan Williams and Britten wrote some wonderful music for Housman and Donne respectively but it’s not obvious that the poems are displayed to great effect. The lyric, therefore, says Sondheim, has to be dense enough to pack in some meaning but loose enough to allow the music to do its work. A blunter way of putting this is that lyrics are not really poetry.

Whatever their status, Sondheim was a master. There are so many examples to choose from but one will have to do. In Together Wherever We Go from Gypsy Sondheim gets two jokes into a single verse, one about dance steps and the other about singing flat. At the same time he manages to deepen the characterisation and take the story on, all the while strictly respecting the discipline of the music. And like a speech, the lyric has to be clear because the audience will only get to hear it once. It’s no surprise that brilliant lyricists are so rare. @PhilipJCollins1

Jargon buster: Trusted

Every company wants to be trusted. Of course they do. If you're a bank, I am trusting you with my money. If you're a supermarket, I trust that your lasagna contains no horse. The mistake so many companies make is to believe that the way to be trusted is to simply declare that you are. Nary a set of corporate values slides by without the word "Trusted" cropping up. There are three problems with this. The first is grammatical. The construction is passive. "Who by?" I am left asking. The silence is deafening. The second is persuasive. There are no words in the English language more alarming than these two: "trust me". The third is philosophical. Baroness Onora O'Neill has spoken incisively on the subject. The financial crisis, she points out, was a crisis of trust, but it was not that we trusted the banks too little, but rather that we trusted them too much. Don't be trusted, therefore, but be trustworthy. Corporate value writers, I present you with a new value, for free: be trustworthy, not trusted. @Joshuahwilliams

When all else fails, speak

Last week, the head of MI6 made a speech. “It is unusual for the holder of this office to give public speeches” declared Richard Moore. “This is something that I want to change.” His timing is revealing. Moore’s sudden appetite for oratory comes in the wake of a string of reputational hits — most recently over the decision by UK spy agencies to host classified data on Amazon’s cloud servers.

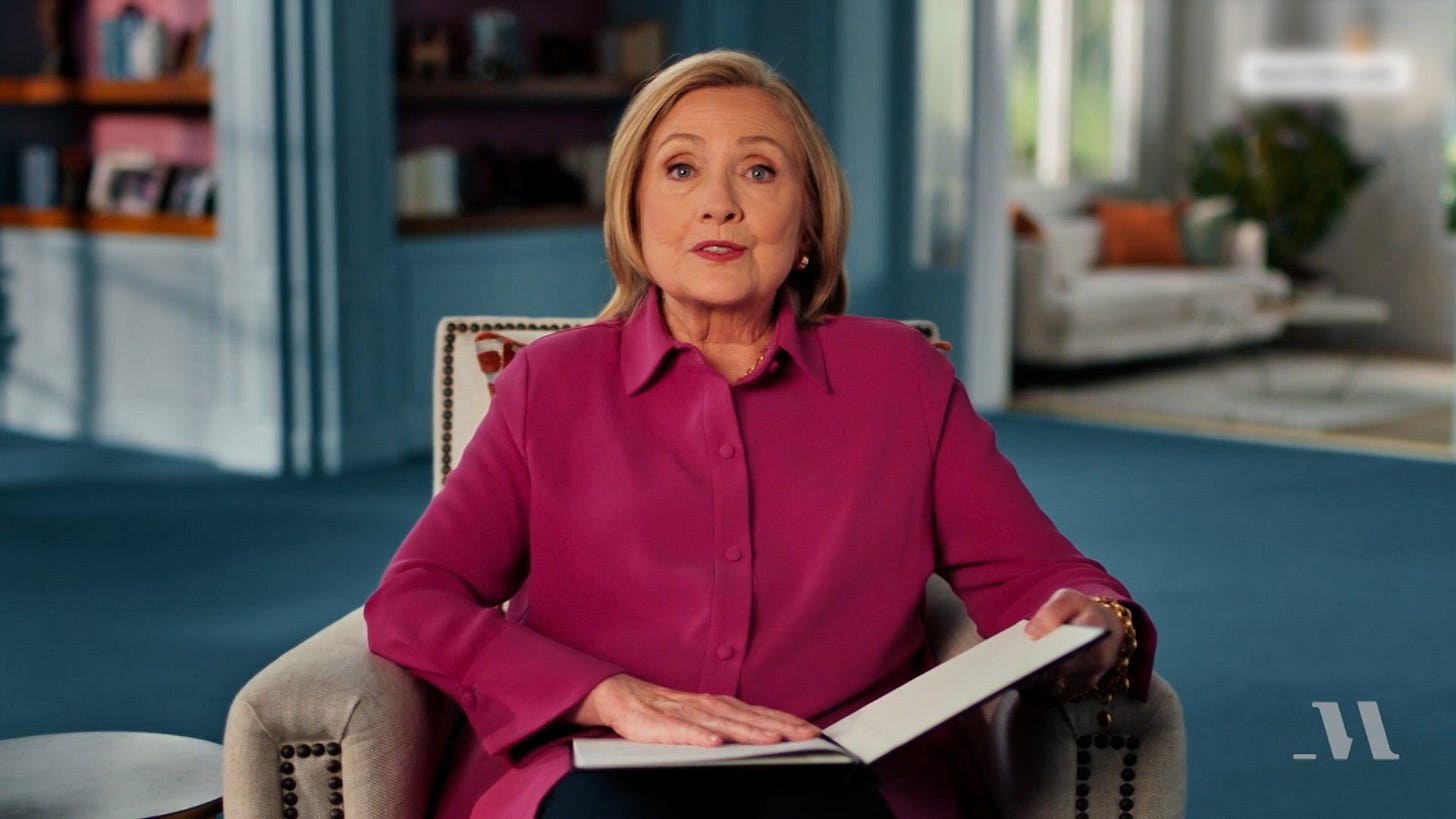

He is not the only unlikely orator to make headlines this month. Hillary Clinton recently gave a glimpse into an alternative political universe when she read her discarded victory speech from the night of the 2016 US election. The clip features in a trailer promoting Clinton’s new online masterclass. But her gimmick is more than just a money maker; since stepping back from the political limelight, Clinton has faced a series of public disappointments. Her recent thriller, co-authored with writer Louise Penny, was roundly mocked by critics and supporters alike (“even airports sell better books than this”).

In times of crisis, leaders are right to seek refuge in rhetoric. A good speech can restore even the most tarnished of reputations. Mark Twain once exclaimed: “what an organ is human speech when it is played by a master!” If the world’s most secretive agency can heed his advice, we all must. @_alice_elliott

Jargon buster: Hero content

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No it’s… a piece of content marketing. The worst jargon conceals dimness behind fake complexity. But another kind casts the ordinary as extraordinary. “Hero content” refers to a blogpost, video or any other marketing material intended to reach a mass audience. Going viral is difficult but to suggest there is anything heroic about it flatters the marketing profession. It is also likely to confuse anyone unversed in marketing speak. Where possible, particularly in communications, talk about your work in a language those outside it can understand. The real heroes stand up for plain English. @AlexDymoke

Language and beyond

Evidence of schizophrenia abounds throughout history and across cultures, argues Will Self in a provocative essay for Harper’s, but the same is not true of trauma. Self says trauma isn’t an eternal and timeless phenomenon, but is instead a response to the “suddenness” of modernity.

“I’ve worked with my peculiar mind and learned how to start with something and revise it until it was publishable, and I’m just going to be real honest about how I do it.” A fascinating interview with Booker winner, short story master and now fellow Substacker George Saunders.

The greatest art is marked more by sincerity than cleverness argues (£) James Marriott in a typically thoughtful column.

The inside story of Spotify Wrapped. What the viral event tells us about our listening habits and attitudes to privacy.

Think jargon is a child of the internet age? Read this article on sixteenth century merchants and think again.

“Is ‘West Side Story’ a Confederate statue? I don’t think so.” Theatre critics debate the complicated cultural legacy of Sondheim’s masterpiece.

“But where it is most praiseworthy, and arguably most significant, is in her personal civility and humility – her inexhaustible resistance to treating politics as a bloodsport, or her opponents as enemies.” Jeremy Cliffe on Angela Merkel in the NS.

The Spectator’s Peter Wood with enjoyable reflections on Strunk and White’s famous style guide. Of the most famous rule “Omit needless words”, Wood says: “A good instructor comes with a pruning hook. But all too many instructors come with a chainsaw. Ideally, you teach students to love words — to sense their contours, their subtle textures and the meanings inside the meanings. To teach the novice to slash away every needless word is to teach the student to hate the richness of language.”

New from us

The migrant crisis could be solved by wit and imagination but this government has neither, argues Phil in his NS column.

The British state may need to be smaller, but it mostly just needs to be better, says Josh in City AM.

How Athens can persuade the UK to return the Parthenon marbles, by Zach in The Critic.

Follow us

Last thing…

At The Draft we’re specialists in writing and rhetoric. We help businesses and public figures make their case more persuasively. If you could use our help, get in touch. And if you enjoy First Draft, forward it on. Thanks for reading.