First Draft #17: a newsletter on public language

Putin’s profanities; ESG hot air; the power of “natural”

Putin and the power of mockery

On the world stage, Putin doesn’t just play dirty, he talks dirty. “It’s your duty, you beauty,” he said this month, referring to Ukraine’s Minsk agreement obligations. The phrase, which echoes a folk saying about sexual submission within arranged marriages, set Russian social media abuzz.

Putin has form with coarse language. In 2015, he accused Turkey of “licking the Americans in a certain place”. In 2006 he said “They've asked me when I began having sex… I don't remember ... I remember exactly when I did it the last time. I can define that right down to the minute.” When a foreign journalist quizzed him on the repression of Chechens, he said the reporter was an Islamic radical, and invited him to be circumcised. He once questioned the sexual proclivities of democracy protesters.

This is a mere sample of bawdy Putinisms. There are many more. But what is his game, other than to put reporters in their place? Putin observer Michele Berdy says it must be deliberate, since he’s otherwise a polished speaker with excellent Russian. Her theory is it is a way of being “one of the guys throwing back beers, and talking about life the way it really is.” Political correctness is despised in Russia, she says. Politicians gain from being the opposite.

I wonder if this is a projection. In a democracy, politicians need to be liked. Electoral punishment awaits the phoney, the wooden, the out of touch. But Russia is not a democracy. Putin’s position relies less on public affection and more on perceptions of his power.

A better explanation for Putin’s rudeness, then, is that rather than making him appear ordinary, it makes him seem extraordinary. Psychological research backs this up. A Dutch study from 2011 exposed test subjects to forms of norm-breaking: office visitors taking coffee without asking; bookkeepers bending accounting rules; restaurant visitors ordering brusquely. It found that when “people do not respect the basic rules of social behaviour, they lead others to believe that they have power.”

Coarse language conveys dominance. In Putin’s recent phrase, the domination was literal and sexual. But the choice to use it signals dominance of another kind. On the world stage, leaders’ elevated rhetoric (the Kenyan UN ambassador's speech on Ukraine is a fine example) conveys reverence for an order that takes precedence over any one nation — an order that Putin’s mockery belittles.

To transgress where others conform projects confidence many construe as power. Putin’s words may be impish, but the intention is serious. @AlexDymoke

Jargon buster: At the heart of

To proclaim that something is “at the heart of” another thing is now practically a corporate religion. Agility is at the heart of necessity. Technology is at the heart of pizza delivery. Blocked drains are at the heart of everyday life. Unfailingly at the heart of things are “people” and “communities”. Meanwhile government ministries compete for the most ludicrous use of the phrase. One agency has “delivering” at the heart of its “delivery plan”. The Northern Powerhouse is at the heart of the Rugby League World Cup. At the heart of good writing is an absence of cliché. Next time you feel yourself reaching for a hearty platitude, transplant another metaphor instead. @_alice_elliott

Warm Words, Hot Air: the cost of corporate moralising

“Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow”

(TS Eliot, The Hollow Men)

The big idea in business in recent years has been ‘stakeholder capitalism’: the idea that businesses are not beholden to their shareholders, but rather to society at large.

Between the idea and the reality, however, a shadow appears. Lucian Bebchuk, a Harvard Law Professor, has long argued the movement is more rhetoric than reality. When America’s corporate elite signed a stakeholder pledge in 2019, it was Bebchuk who spotted that only 2 percent had consulted their boards beforehand, suggesting they had no real intention to change how they behave.

More recently, Bebchuk analysed 100 company acquisitions, worth over $700bn, many of them conducted by companies preaching the stakeholderist rhetoric of “ESG” (meaning: good for the environment, good for society, and following good corporate governance).

Bebchuk reported that these acquisitions resulted in “large gains for shareholders” and “substantial private benefits for corporate leaders”. For other “stakeholders”, the returns were less positive: no new protections for employees or payment for those due to be laid off. None either for customers, suppliers, communities, the environment or any other stakeholder.

Does it matter that the prophets of stakeholderism are producing little more than hot air? Aren’t warm words helpful, if they shift the debate?

Tariq Fancy, who once ran responsible investing at private equity behemoth Blackrock, says no. In an eviscerating series of essays on the subject, he argued that ESG rhetoric does real harm because it gives the impression that companies are capable of handling huge societal challenges (like climate change) alone, and that further legislation or regulation (which would hamper their businesses) is not required. In short: that spouting the rhetoric of ESG is really a cover for serving shareholders, society be damned.

That brings us back, neatly enough, to Eliot’s ‘Hollow Men’:

“This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper”

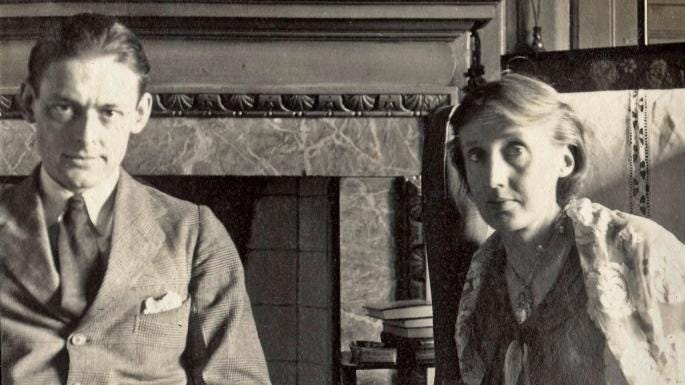

Echoes from 1922

We have entered the centenary of one of the great years in the history of literature. James Joyce’s Ulysses, TS Eliot’s The Waste Land and Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room were all published in 1922. It was the year in which Marcel Proust died but Kurt Vonnegut, Philip Larkin, Jack Kerouac and Kingsley Amis were born. So, for that matter, were Just William and Mickey Mouse. But there is a more sinister echo in the air as I write these words. One hundred years ago this year, the BBC began its radio service in the United Kingdom. One of the first news items it reported on was the creation, on December 30th 1922, of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. @PhilipJCollins

Jargon buster: To impact

The metamorphosis of nouns into verbs is one of the joys of language. Shakespeare was a master. “Why, what read you there/ That have so cowarded and chased your blood” says Henry V. But it isn’t just Shakespeare. We invent new verbs all the time. Words like “trolling”, “googling”, and “gaslighting” all began life as nouns. But sometimes “verbing” goes wrong. Last month, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek apologised to staff for the anti-vax flirtations of his star podcaster. “There are no words,” he said, “to adequately convey how deeply sorry I am for the way The Joe Rogan Experience controversy continues to impact each of you”. “To impact” jars for two reasons. First, impacts are discrete; they do not “continue”. Second, people do not speak like that. We talk of being “affected”, not “impacted”. Which leads to a central point about verbing. Verbing is welcome when it adds a new action to the language (or, in Shakespeare’s case, paints a poetic image); but less so when it gives a technocratic spin to concepts that already exist. Ek, leave the verbing to the Bard. @zachdhardman

Nature’s advantage

To be called “natural” is a boon. A wealth of social science research shows products labelled as such are seen as healthier and less environmentally harmful. Now, a study from Yale’s Program on Climate Change Communication has revealed a similar effect with gas. The paper, published last year, tested names for natural gas on 3,000 Americans. It found we respond more positively to “natural gas” than other terms such as “methane”, “methane gas” and “fossil gas” (natural gas is almost entirely methane). This backs up earlier research that found 76 percent of Americans view natural gas favourably, compared to 51 percent for oil and 39 percent for coal.

Perhaps surprisingly, “natural gas” wasn’t coined by the marketing departments of energy corporations. Instead it emerged naturally in the 19th century as a way to distinguish from new forms of artificial gas. Now campaigners are seeking change. Matt Vespa, a lawyer for sustainability group Earthjustice, said recently: “I want my language to communicate the harms that are inherent in methane.” Natch. @AlexDymoke

Language and beyond

A comprehensive reading list for learning about the Ukraine crisis.

“It appears to be the only language boasting more than 200 million speakers that has more second-language speakers than native ones.” From obscure island dialect to Africa’s most spoken language — Harvard professor John Mugane on the unstoppable rise of Swahili.

“It’s easier to identify an individual’s linguistic ‘signature’ than it is to do the same thing for a whole social group—especially one as large and internally diverse as ‘women’ or ‘men’.” Are there stylistic differences between women’s writing and men’s? This blog tackles a thorny question.

“Never before in history have new tracks attained hit status while generating so little cultural impact.” Is old music devouring new music? Fascinating post from Ted Gioia (hint: yep, it is.)

An alphabetised history of writing.

TS Eliot and the origins of the cryptic crossword — lovely piece by Roddy Howland Jackson.

“Can Russia Actually Control the Entire Landmass of Ukraine?” A David Patraeus Q&A in the Atlantic draws on the general’s experience in Iraq.

A witty and beautiful essay on old age by Roger Angell: “My conversation may be full of holes and pauses, but I’ve learned to dispatch a private Apache scout ahead into the next sentence, the one coming up, to see if there are any vacant names or verbs in the landscape up there. If he sends back a warning, I’ll pause meaningfully, duh, until something else comes to mind.” It was published in 2014, when he was 93. He’s still going at 101. To write like this at any age would be a gift.

New from us

Inflation will puncture overvalued tech giants says Josh in City AM.

Let the Queen retire says Phil in the New Statesman.

Follow us

Last thing…

At The Draft we’re specialists in writing and rhetoric. We help businesses and public figures make their case more persuasively. If you could use our help, get in touch. And if you enjoy First Draft, forward it on. Thanks for reading.