First Draft #28: a newsletter on public language

Writing by hand; “Lived experience”; Military idioms; Biden’s diplomacy

The fall and rise of handwriting

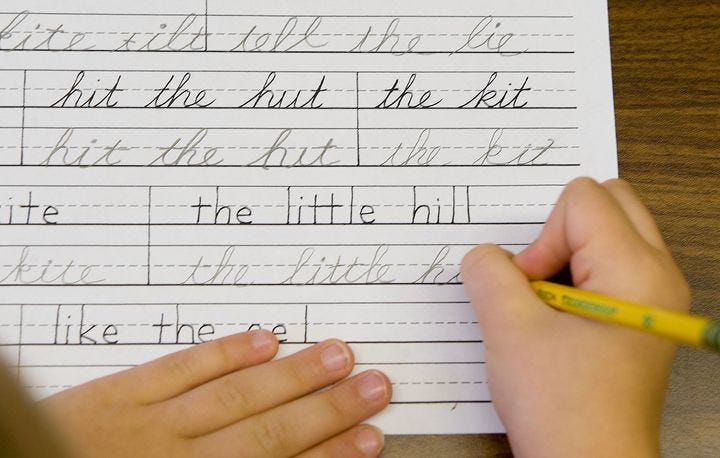

Since the dawn of the laptop age, penmanship – the art of writing by hand – has seemed destined to follow typewriters and vinyl records: relics prized more for their tactile charm than their usefulness. But growing research, particularly into how we study, suggests we may have been hasty to end our scribbling. For retention and comprehension, it appears the pen is mightier than the keyboard.

Evidence of the decline of handwriting abounds. Recent surveys found one in 10 had written nothing by hand in over a year, while a quarter of young people had never written a letter or diary entry. Many aged 18-24 have never even written a card or to do list by hand. The UK curriculum no longer prescribes the teaching of cursive (joined up) writing. Meanwhile, classrooms and lecture halls echo with the rattle of keyboards.

One area penmanship has held firm against computers is exams. But handwriting is no longer safe even in the hush of the assessment hall. This week top exam board AQA announced digital GCSEs are but a few years away, a shift that once moved novelist Colm Tóibín to bemoan the decline of the “identity-forming” skill of handwriting.

But the lone cries of novelists are steadily being joined by a chorus of academics, parents and policy-makers. As the Economist recently reported, a growing body of research confirms unique advantages to penmanship, particularly in education. A 2014 study found students with laptops took more voluminous notes, but “performed worse on conceptual questions”, suggesting they are merely transcribing what they hear, rather than understanding it.

It seems the very ease of typing seals its inferiority as a study aid. Handwriting is slow. This slowness forces us to take shortcuts, which amount to little acts of translation. The activeness of this process — of turning long form ideas into shorter ones — helps things lodge in the mind. In other words it is possible, and indeed tempting, to type mindlessly. Handwriting, meanwhile, makes us think.

No wonder policy-makers are returning to penmanship. Sweden’s education minister recently announced the end of digital learning before the age of six. In the US, half of states mandate compulsory handwriting lessons, despite no national requirement to do so since 2010.

It may be too early to claim a reversal of the end of handwriting. But some clearly realise that for some kinds of learning the pen really is the mightiest instrument of all. @AlexDymoke

Jargon buster: Lived experience

“Lived experience”, which is steadily seeping from social sciences and psychology into everyday use, is meant to distinguish between firsthand experiences and those acquired secondhand or vicariously. The problem is even vicarious and secondhand experiences are, by definition, lived. Which is why we have the more precise “firsthand” and “direct” to convey this distinction. The movement to pay special attention to those with direct experience of certain traumas and prejudices is a noble one. But it is done no favours by twee, logically flawed language like “lived experience”. @AlexDymoke

“Got your back” and other military idioms

The roots of a surprising number of idioms lie in the fields of distant wars. In the First World War, to be on “the front line” was to stand guard in the first of several rows of trenches. When Conservative MPs call victory in 2024 a “long shot”, they are harking back to the early days of naval warfare, when cannons were accurate only at short range.

The military roots of some phrases are immediately obvious – think “AWOL” and heads “above the parapet”. But others we barely notice, such as “top brass”, the “whole nine yards” and a “flash in the pan”. These are what George Orwell called “dying metaphors”: those which have “lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves”.

A figure of speech in Joe Biden’s 10 October statement on Hamas’s attack on Israel demonstrated something Orwell never considered. “Let there be no doubt”, the President said: “the United States has Israel’s back.” In the Second World War, “to have someone’s back” meant to provide covering fire for a comrade’s exposed side. By using the phrase to convey support for an ally at war, Biden brings the idiom close to the original battlefield meaning, thereby restoring its potency. Sometimes, his turn of phrase reminds us, metaphors can be raised from the dead. @HibbertLizzie

Joe Biden: under-rated diplomat

President Biden is often mocked for being voluble. Rather like Neil Kinnock whose speech (“why am I the first Biden in a thousand generations”) he once “borrowed”, Biden is often said to talk without any clear destination at the end of his paragraphs. That this is unfair, and that Biden is severely under-rated as political communicator, should now be obvious. In the most trying, indeed tragic, of circumstances he rose. Arriving in Israel to conduct hasty and difficult diplomacy, Biden spoke in solidarity, with moral clarity.

Biden drew immediate criticism for his suggestion that the attack on the hospital in Gaza City looked as if it “was done by the other team”. The attack came in at once that Biden must think the conflict is a game, but of course he thinks no such thing. It may be that by describing the attack in such a way Biden gently puts a little distance between the USA and the conflict. He didn’t, after all, say “it was them”. It’s a folksy description which could have come from Ronald Reagan or George W. Bush.

Biden does empathy better than any senior politician of his generation (and he alone spans two generations). He has known tragedy in his own life and he draws on it to make emotional connections. Like America after 9/11, he said, Israel will be feeling “Shock. Pain. Rage. An all-consuming rage”. Yet rage can lead, as it did in the American case, to mistakes which is a gentle way to usher in a diplomatic request for aid to be delivered to Gaza via Egypt, something to which the Israeli cabinet has since assented. In the midst of war it might be only a small success but there is no doubt that the maligned President stood up when it counted.

Perhaps in imitation of President Biden, Rishi Sunak offered his own sporting metaphor to Benjamin Netanyahu. After pledging continued friendship and support in the standard way, Sunak added rather awkwardly “and we want you to win”. Win what, exactly? That really did make the conflict sound like a game. @PhilipJCollins1

Language and beyond

While researching a speech we stumbled upon this interesting tidbit from an article (£) in The Atlantic: “Over the course of the 20th century, words relating to morality appeared less and less frequently in books: According to a 2012 paper, usage of a cluster of words related to being virtuous also declined significantly. Among them were bravery (which dropped by 65 percent), gratitude (58 percent), and humbleness (55 percent).”

An interesting thread explains why so many news outlets slipped up while reporting on the explosion at Al Ahli hospital in Gaza.

As speechwriters, we know all about misattributed quotes, but this is a doozy: Dublin marathon medal has wrong Yeats quote.

A provocative defence of cliches from a 1958 edition of the New York Times.

An academic gives a balanced overview of the vexed debate over whether news organisations should call Hamas and similar groups terrorists.

A beautiful piece of writing about losing a parent in childhood. See also the comments beneath the article, many of which are as eloquent and moving as the piece itself.

Great piece from novelist Michael Faber on the perpetual struggle of tinnitus: “Mostly, people just learn to live with the humiliations that afflict their ears (and their eyes and their joints and their teeth) as they grow older. They have to.”

Kabul under the Taliban through the prism of one luxury hotel.

New from us

Phil on Sir Keir Starmer’s winning story for Britain.

Follow us

Last thing…

At The Draft we’re specialists in writing and rhetoric. We help businesses and public figures make their case more persuasively. If you could use our help, get in touch. And if you enjoy First Draft, forward it on. Thanks for reading.

"Win what exactly", Philip asks, suggesting that Rishi Sunak was making a sporting analogy about the situation in Israel and Gaza. But is that really what Sunak was doing? He was speaking about a war. He was making it clear that he wasn't calling for a ceasefire. He wanted Israel to win. I can understand that Philip might disagree with the policy. I don't understand why he finds the words difficult to comprehend. Sometimes a politician can just mean what he or she says.